Drop the brand, talk about the mechanism

Have you ever been stuck furiously debating a technical methodology, but you talk past each other, frustrated and unmoved? The solution is often surprisingly simple: ditch the brand names, and talk about how things work instead.

The trouble with brand names

Every popular methodology needs a name, or it would be impossible to talk about, or build a following. You can name OO, Agile, DDD, TDD, FP, DevOps or a hundred other popular ideas, which for most developers will instantly summon a bundle of concepts, impressions, and experiences. Much of this will be relatively consistent, so even strangers can have productive, informed conversations. Great!

The trouble is, of course, when it isn’t. These famous traditions were each founded in a few years or decades by a fairly small group of people, propelled by a solid shared vision. But when your creation escapes into the popular consciousness, it doesn’t really belong to you anymore. Successful ideas have a life of their own!

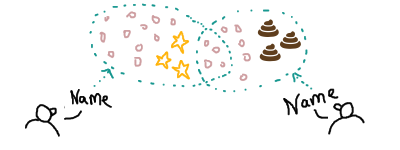

With hundreds, thousands, millions of adherents and critics, it’s impossible to stop the name’s meaning drifting, like a flag in sand. Beginners are drawn to the excitement of a new paradigm, perhaps enticed by a sense of novelty, or a fantasy of release from the friction of daily work. Weather-worn types might pick out the bits that are supported by their experience. Online types will be attracted by personality, debate and controversy. People with something to sell will find some aspects more marketable than others. At some point, the memetic nuggets jostling under the umbrella become so inconsistent that the risk of major misunderstandings can’t be ignored.

Can’t people just use the name for the REAL thing?

Abigail: This is a simple thing, I’ll make a class with some immutable fields and two calculation methods.

Barnaby: You’re doing it wrong, real OO is meant to be like biological cells sending messages. You need void methods and state.

Abigail: Since when? There’s a constructor, private fields, an interface, methods…. that’s classic OO!

One of the most futile ways to burn your time is to pine for the days when everyone used the words in the same way; fighting battle after battle to defend the boundaries of the real meaning of the name. No-one has ever won one of these battles. They are uniformly draining and unproductive to wade in to, as they are boring to witness.

Sometimes this process of change is better viewed as natural evolution, rather than the erosion of virtue into vice. Alan Kay, the titan who introduced “object oriented” to our vocabulary in the 1970s famously said:

OOP to me means only messaging, local retention and protection and hiding of state-process, and extreme late binding of all things.

This was closely tied to his language Smalltalk, and the idea of biological cells sending messages to each other. Who would choose this definition now? Do we really want every unit of code to behave like an amoeba, or a microservice? Smalltalk inspired children like Java and Ruby, grandchildren and great-grandchildren, hundreds of languages that now collectively dominate the industry with different flavours, priorities and ideas. Who is served by Kay’s bold 70s research ideas being the “real” OO?

Or at least, that’s a view you could take. Note that Kay himself focuses on the mechanisms rather than the “object” brand, which makes the ideas easier to grapple with. Here’s another view: who cares? If the underlying techniques work in a way that solves your problem, we don’t need to worry what umbrella they sit under, nor what it is called. By wasting time bickering about the “real” meaning of the brand name, Abigail and Barnaby buried what should have been an interesting conversation about objectives and tradeoffs with a useless turf war.

Baggage handling

Cassie: Shouldn’t we really be using TDD?

Denis: We did TDD at the last place I worked, and it sucked! Complete waste of time, and the tests were all garbage.

Cassie: I bet you didn’t do it right. Studies have shown that TDD improves code! All the biggest thought leaders recommend TDD.

Denis: Pff, what a bunch of hype! We don’t need to be zealots.

When a popular methodology has been around for a while, many people that you talk to will have had first- or second-hand experience in applying it. Beware! You can’t argue with this; they were there, after all. Of course, what they saw might not remotely resemble the thing that you’re trying to argue for.

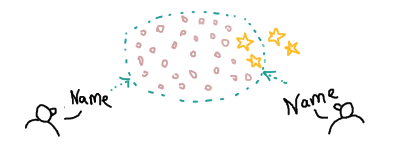

Using the brand name here is a trap - while you might have a clear idea of what you mean, you are blundering into an invisible and unmovable wall of bitter happenstance, and eagerly tarring yourself and your viewpoints with it.

Let’s repeat the conversation using the mechanism instead instead of the brand:

Cassie: Hmmm, picking the right module boundaries sure is tough here. Why don’t we stop and write a test - it’ll keep us honest with working code while we experiment.

Denis: Sure, that could work.

Cassie and Denis have something in common - they care about software design. By focusing on the mechanism that makes TDD tick – writing tests first to drive design and enable safe refactoring – they could swiftly agree on an approach as if they’d discovered it themselves, without tripping over Denis’ anecdotes about something called “TDD”.

On the other hand, if Denis didn’t care much about software design - the first conversation would have crashed in the same way, but the second would have revealed the problem, allowing Cassie to reset her expectations and understand how to work together better.

The enthusiast’s trap

Eric: Great, we’re allowed to run Invoice Consolidation as an Agile Project!

Fatima: I love it! I’ll set up the daily standups, story kickoffs, desk checks, retros, burnup charts, information radiators, sprint planning, backlog grooming, and weekly showcase.

Eric: I’m so glad we’re finally putting people over process!

People that deeply understand and love the methodologies that we use are so valuable in a thousand different ways, but no good deed goes unpunished - there are traps waiting just for them.

Each methodology can contain hundreds of ideas and practices, each thematically related but with distinct benefits, costs and tradeoffs. They are often layered, incrementally built on each other in generations of practice and published writing, based on differing individual experiences, studies and external pressures. Each one has been useful to someone at some point, but not necessarily at the same time and not necessarily to you.

The enthusiast’s trap then is a kind of logical fallacy; We need to achieve A; methodology B can help us achieve A; C is an idea associated with B, therefore we should do C. An enthusiast’s blind spots are not born of ignorance, but of an overeagerness to adopt ideas they like without the sceptical rigour they would sensibly apply to others.

Overly dwelling on the brand name here primes the trap; it emphasises the big bucket of ideas rather than the objective, and fosters groupthink between likeminded people.

Eric and Fatima were supposed to figure out “How can an Agile approach help customers with their invoices?” and they never got past “How can we Agile?”. Focusing more on what these practices are supposed to do might have led to a slimmer approach focused on customer outcomes.

Sell the cure, don’t sell the medicine

Gemma: So we’ll just loop through these menu items…

Harald: No, we’re doing functional programming, so we don’t write loops. You need to use recursion, but you can use tail recursion here so we don’t blow the stack.

Gemma: Isn’t that… the same thing but harder?

Harald: No no, it’s the only way to achieve referential transparency! It’ll be easier in the long run!

Gemma: …

Harald: I mean, now you get equational reasoning, it’s declarative.

Gemma: …

Have you noticed that ads for medicine on TV never bang on about clinical trials or their finger-length Greek word made of rare Scrabble letters? Instead they show someone playing with their dog and riding a bike - the kind of things you would like to do when you feel better.

Speaking in the language of things people actually want is not “dumbing down” and it’s not shameless pandering: it helps to keep you honest. It’s easy to get distracted by rabbit holes of detail, especially shielded by the indirection of a brand name. Let’s give Harald another chance:

Gemma: So we’ll just loop through these…

Harald: OK, sure. There’s other ways to do this, but let’s tuck the result list into the inner scope so no-one else can see it; that way from the outside they can only see the input and the output, they can’t touch the mutable thing. It’s safer, and it’ll be easier to test and plug this code into other things later.

Gemma: Sure, good idea. Now on to the next thing…

Harald is doing two new things here: he’s respecting that Gemma is trying to solve a particular problem, and he’s talking about a select minimum of FP mechanisms in a way that directly connects them to the solution. Gemma might ask more questions later and be willing to go deeper – or not – but for the time being she has a direct line of sight to the problem, and a solution that has been improved in particular ways.

By focusing on the cure instead of the medicine – mechanism instead of brand – opinions could be swayed and progress made, without waste and confusion.

Conflict to consensus to outcomes

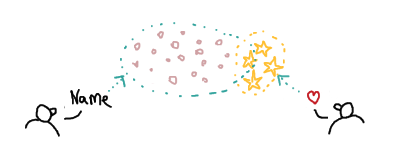

Of course it’s useful to have names for ideas that drive our work, especially if some group of people can agree on the meaning. All the more reason to aware of the pitfalls! In all of the examples we’ve looked at, overuse of a popular brand name was an obstacle to one or both of:

- Reaching a consensus about what to do;

- A clear focus on actual desired outcomes.

My favourite story about this is when Reagan and Gorbachev famously met in Geneva in the height of the Cold War, after months of failed negotiations. The breakthrough finally came not through arguing the merits of their -isms and -ocracies, but by considering a ludicrous imaginary scenario - would you defend us if we were attacked by aliens? Having established that they both would, they were able to work backwards from this infitesimal speck of common ground, lowering tensions and restoring a level of cooperation that eventually led to nuclear disarmament treaties.

What’s your “alien invasion”? Often, it’s some version of “we are good people and we like good things”. Everyone is the hero in their own story, and likes to think of themselves as fighting the good fight. Refusing to get stuck in the -isms and -ocracies of software development is often the first step to getting the results that you really want.